The emerging-market slowdown is not the beginning of a bust. But it is a turning-point for the world economy This marks the end of the dramatic first phase of the emerging-market era, which saw such economies jump from 38% of world output to 50% (measured at purchasing-power parity, or PPP) over the past decade. Over the next ten years emerging economies will still rise, but more gradually. The immediate effect of this deceleration should be manageable. But the longer-term impact on the world economy will be profound.

This marks the end of the dramatic first phase of the emerging-market era, which saw such economies jump from 38% of world output to 50% (measured at purchasing-power parity, or PPP) over the past decade. Over the next ten years emerging economies will still rise, but more gradually. The immediate effect of this deceleration should be manageable. But the longer-term impact on the world economy will be profound.

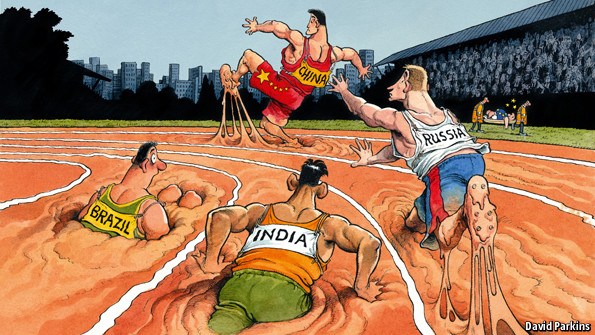

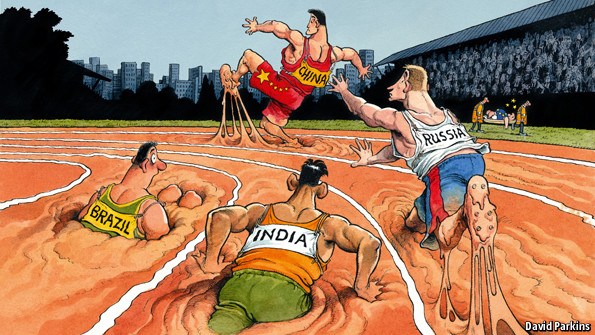

China will be lucky if it manages to hit its official target of 7.5% growth in 2013, a far cry from the double-digit rates that the country had come to expect in the 2000s. Growth in India (around 5%), Brazil and Russia (around 2.5%) is barely half what it was at the height of the boom. Collectively, emerging markets may (just) match last year’s pace of 5%. That sounds fast compared with the sluggish rich world, but it is the slowest emerging-economy expansion in a decade, barring 2009 when the rich world slumped.

Running out of puff

In the past, periods of emerging-market boom have tended to be followed by busts (which helps explain why so few poor countries have become rich ones). A determined pessimist can find reasons to fret today, pointing in particular to the risks of an even more drastic deceleration in China or of a sudden global monetary tightening. But this time a broad emerging-market bust looks unlikely.

China is in the midst of a precarious shift from investment-led growth to a more balanced, consumption-based model. Its investment surge has prompted plenty of bad debt. But the central government has the fiscal strength both to absorb losses and to stimulate the economy if necessary. That is a luxury few emerging economies have ever had. It makes disaster much less likely. And with rich-world economies still feeble, there is little chance that monetary conditions will suddenly tighten. Even if they did, most emerging economies have better defences than ever before, with flexible exchange rates, large stashes of foreign-exchange reserves and relatively less debt (much of it in domestic currency).

That’s the good news. The bad news is that the days of record-breaking speed are over. China’s turbocharged investment and export model has run out of puff. Because its population is ageing fast, the country will have fewer workers, and because it is more prosperous, it has less room for catch-up growth. Ten years ago China’s per person GDP measured at PPP was 8% of America’s; now it is 18%. China will keep on catching up, but at a slower clip.

That will hold back other emerging giants. Russia’s burst of speed was propelled by a surge in energy prices driven by Chinese growth. Brazil sprinted ahead with the help of a boom in commodities and domestic credit; its current combination of stubborn inflation and slow growth shows that its underlying economic speed limit is a lot lower than most people thought. The same is true of India, where near-double-digit annual rises in GDP led politicians, and many investors, to confuse the potential for rapid catch-up (a young, poor population) with its inevitability. India’s growth rate could be pushed up again, but not without radical reforms—and almost certainly not to the peak pace of the 2000s.

Many laps ahead

The Great Deceleration means that booming emerging economies will no longer make up for weakness in rich countries. Without a stronger recovery in America or Japan, or a revival in the euro area, the world economy is unlikely to grow much faster than today’s lacklustre pace of 3%. Things will feel rather sluggish.

It will also become increasingly clear how unusual the past decade was (see article). It was dominated by the scale of China’s boom, which was peculiarly disruptive not just as a result of the country’s immense size, but also because of its surge in exports, thirst for commodities and build-up of foreign-exchange reserves. In future, more balanced growth from a broader array of countries will cause smaller ripples around the world. After China and India, the ten next-biggest emerging economies, from Indonesia to Thailand, have a smaller combined population than China alone. Growth will be broader and less reliant on the BRICs (as Goldman Sachs dubbed Brazil, Russia, India and China).

Corporate strategists who assumed that emerging economies were on a straight line of ultra-quick growth will need to revisit their spreadsheets; in some years a rejuvenated, shale-gas-fired America may be a sprightlier bet than some of the BRICs. But the biggest challenge will be for politicians in the emerging world, whose performance will propel—or retard—growth. So far China’s seem the most alert and committed to reform. Vladimir Putin’s Russia, by contrast, is a dozy resource-based kleptocracy whose customers are shifting to shale gas. India has demography on its side, but both it and Brazil need to recover their reformist zeal—or disappoint the rising middle classes who recently took to the streets in Delhi and São Paulo.

There may also be a change in the economic mood music. In the 1990s “the Washington consensus” preached (sometimes arrogantly) economic liberalisation and democracy to the emerging world. For the past few years, with China surging, Wall Street crunched, Washington in gridlock and the euro zone committing suicide, the old liberal verities have been questioned: state capitalism and authoritarian modernisation have been in vogue. “The Beijing consensus” provided an excuse for both autocrats and democrats to abandon liberal reforms. The need for growth may revive interest in them, and the West may even recover a little of its self-confidence. THE ECONOMIST

No comments:

Post a Comment